Context

If you have any interest in airway management – and the fact that you are reading a blog on the TEAM website would suggest you do – then you probably will have heard of the Vortex Approach. Conceived by some very clever clinicians down in sunny Australia, this approach to acute airway management is specifically designed to be used during the time critical evolving airway emergency. It aims to provide a simple and consistent template that can be readily understood and implemented by all clinicians involved in advanced airway management.1

But in a world already full of airway guidelines, airway discussions and a great deal of airway debate, does this approach represent a novel game changer or another pathway to add to the confusion?

Warning

Before we discuss the Vortex Approach to airway management, we should make one thing clear. The available evidence appears suggests that the best way to have a poor outcome in any emergency airway situation, is to have different team members following different plans and with different priorities, irrespective of the proposed airway plan.2,3

The Vortex is a simple and elegant approach to airway management. However, it is a differentapproach to that which many are familiar with, and therefore will run the risk of mistakes being made by lack of familiarity or a cohesive shared mental model.

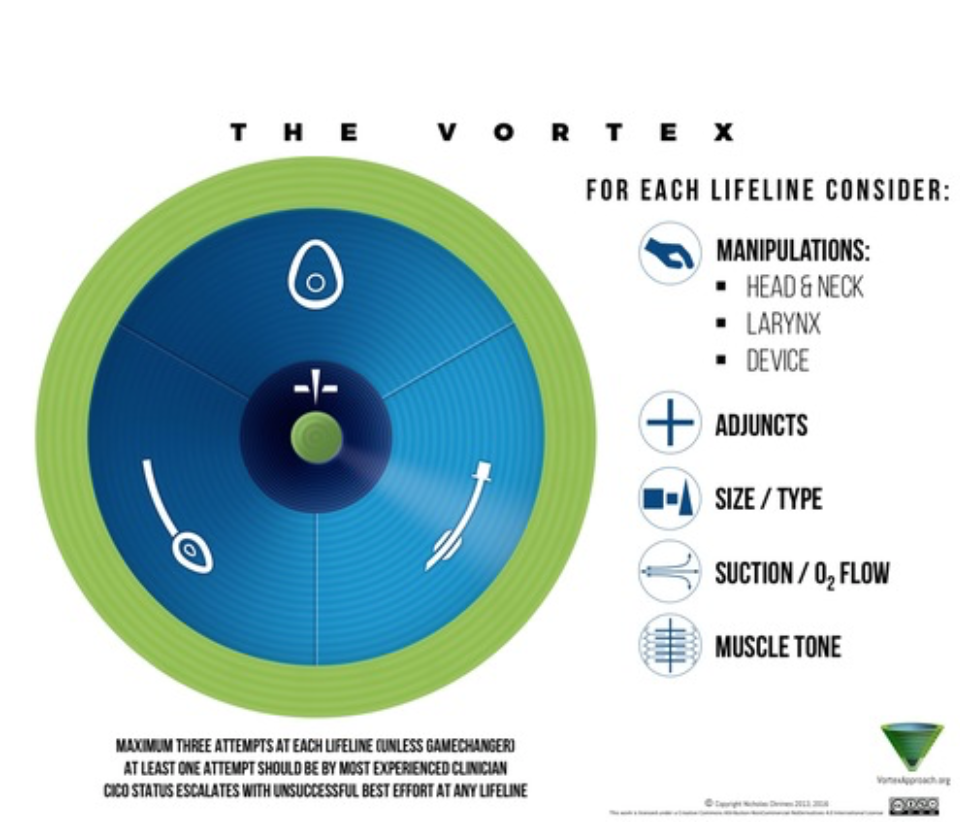

Figure 1 – The Vortex1

Should you wish to follow this approach, it is most likely to run smoothly and improve patient care when applied as an institutional change, rather on a personal ad hoc basis.

Basic Idea

The Vortex Approach is derived from 2 basic principals

- There are 3 ways to achieve and confirm alveolar oxygenation using normal anatomy; a facemask, an endotracheal tube, and a supraglottic device. Should these fail then a front of neck approach is needed.

- Even experienced and well-prepared airway clinicians can be unsuccessful at attempts of simple interventions and make mistakes under pressure.

Method

When using the Vortex, either as an emergency response to unpredicted airway difficulty or as the plan for predicted difficult airway, the team leader should announce something along the lines of –

“this is an emergency /difficult airway situation – we will be using the Vortex approach”

The rest of the team is now aware of the ‘activation’ of the Vortex.

The team then has 3 attempts to achieve oxygenation using each of the three avenues or ‘lifelines’, – facemask, supraglottic device and ETT. These attempts can be done in any order as directed by the clinical situation.

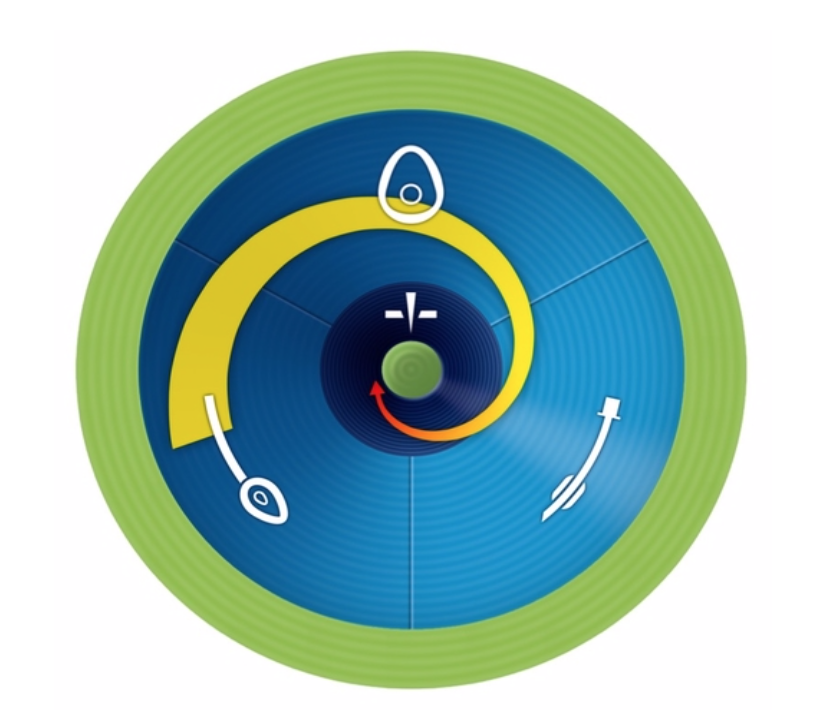

This is conceptualised as moving around the spiral of the vortex towards the centre (figure 2).

Figure 2 – Moving within the vortex1

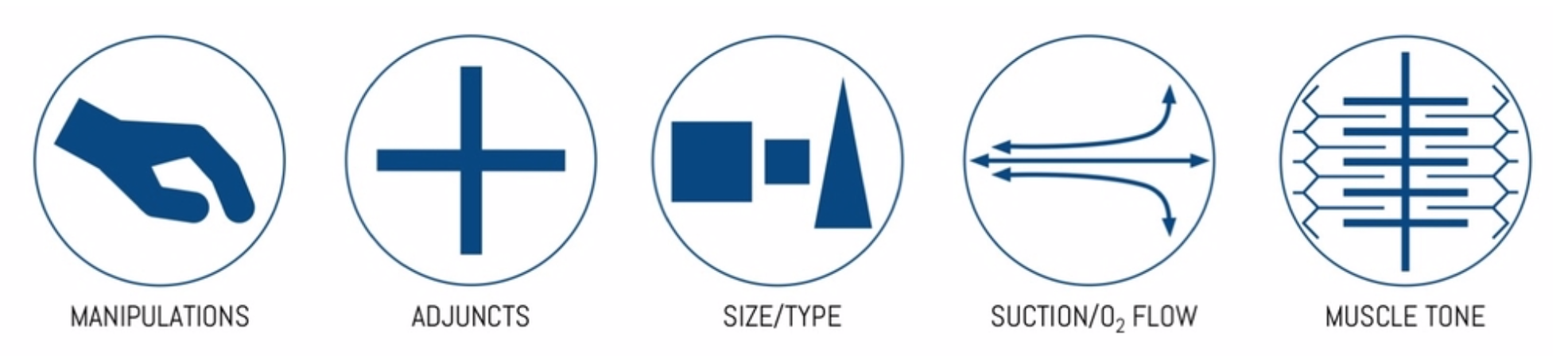

Each time a lifeline attempt is repeated then something should be changed or optimised. The Vortex Approach suggests 5 categories of optimisation (shown below in figure 3) to be considered when attempting a particular lifeline, they will not all apply in every clinical situation and it is up to the team and airway operator to decide which to enact. The Vortex also allows for a ‘game changer’ such as a senior airway doctor’s arrival. In this circumstance a further attempt can be indicated even if the previous three attempts have been unsuccessful.

Figure 3 – Categories of optimisation1

In the unlikely event that alveolar oxygenation is not achieved despite 3 attempts at each of the 3 lifelines then the spiral has reached the centre of the vortex, this then mandates a front of neck approach to recue the situation.

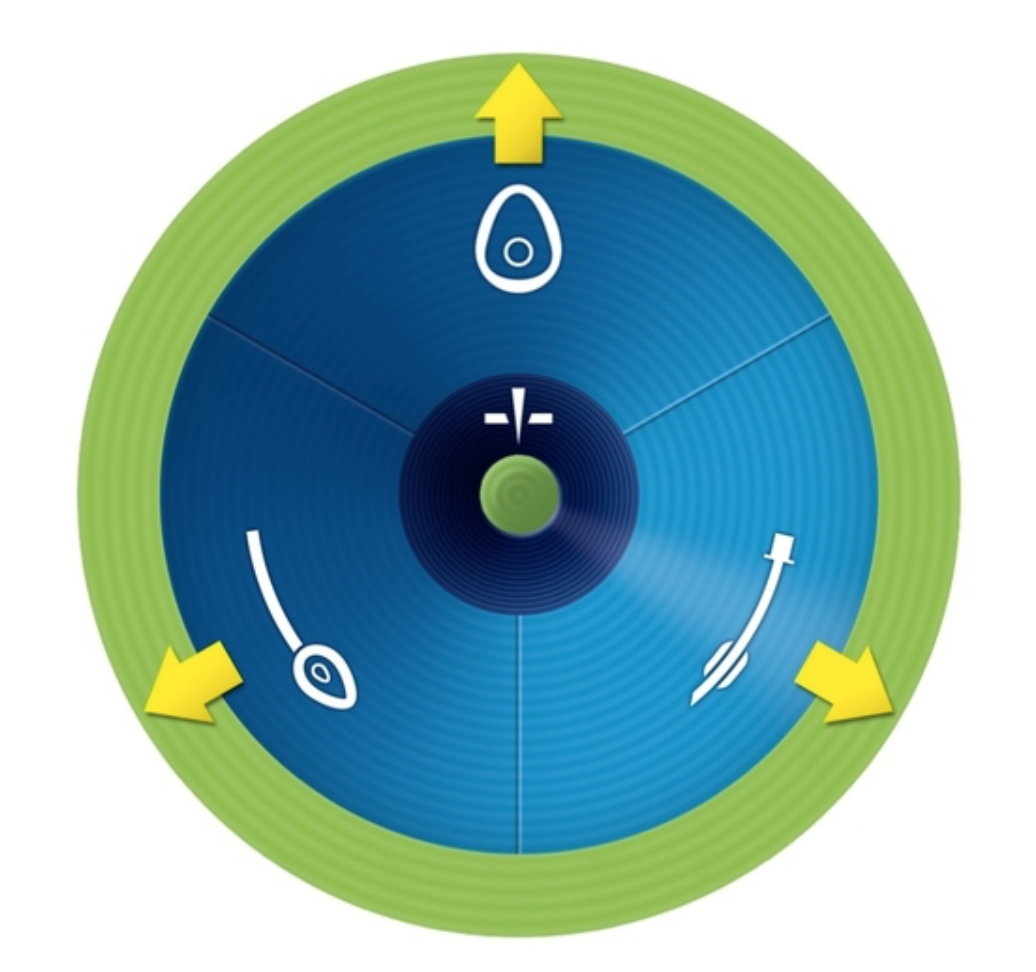

Should oxygenation be achieved at any point then you ‘exit’ the vortex into the ‘safe zone’. Here the team has the time to re-assess and take stock of the situation (figure 4).

Figure 4 – Exiting the vortex into the safe zone1

Figure 4 – Exiting the vortex into the safe zone1

Different to DAS?

So you may ask why do we need a new difficult airway approach? The Difficult Airway Society Guidelines published their latest guidelines on this in 2015, founded on published data and expert opinion,4how does the Vortex Approach differ from this?

To address this concern it is worth noting that at no occasion has the Vortex Approach been suggested to supersede or replace in any way the DAS guidelines. In fact the 2015 DAS publication in The British Journal of Anaesthesia describing the latest iteration of their guidelines, notes that the algorithms that accompany the DAS guidelines are intended as teaching and learning tools and, unlike the vortex, have not been specifically designed as prompts during an airway crisis. Conversely the Vortex describes itself as a “high-acuity implementation tool“ designed specifically to support teamwork and decision-making in the time critical airway emergency.1

Does it work?

This is a tricky question, as airway emergencies tend to be rare. They are high acuity but low frequency events, and as such good evidence is hard to come by.

There are a handful of case reports out there describing favourable outcomes when using the Vortex both in hospital and in the pre-hospital world,5,6 and several anecdotal accounts of its advantages,7,8however to date no good quality evidence exists showing it to be effective.

Final thoughts?

The Vortex is a simple and elegant tool designed specifically for use in the acute airway emergency. As yet there is a paucity of evidence as to its real world application, however as a tool it would seem to be easily understood and readily implementable in modern medicine.

Having said this, is remains likely that currently more clinicians in the UK will be aware of the DAS guidelines and a standard Plan A,B,C etc. Therefore it would be unwise for the lone clinician in an emergency situation to suddenly state to the team they were “entering the Vortex” unless it was institutionally agreed that this was how to manage the airway crisis.

In summary – understand the Vortex, but don’t get sucked in.

References

- Chrimes, N. & Fritzt, P. (2016) The Vortex Approach. [online] Available at:http://vortexapproach.org[accessed 12/06/2019].

- Benger, J., Kirby, K., Black, S. et al.Effect of a Strategy of a Supraglottic Airway Device vs Tracheal Intbation During Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest on Functional Outcome.JAMA. 2018; 320 (8) 779-791.

- Jabre, P., Penaloza, A., Pinero, D. et al. Effect of bag-mask ventilation vs endotracheal intubation during cardiopulmonary resuscitation on neurological outcome after out of hospital cardiorespiratory arrest: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018; 319 (8) 779-787

- Ferk, C., Mitchell, V., McNarry, A. et al. Difficult Airway Society 2015 guidelines for management of unanticipated difficult intubation in adults. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2015; 115 (6) 827-848.

- Le Cong, M. (2014) Vortex Approach in Pre-Hospital Care – a case report. [online] Available at: https://prehospitalmed.com/2014/06/21/vortex-approach-in-prehospital-care-a-case-report/Accessed 12/06/2019.

- Sillen, A. Cognitive tool for dealing with unexpected difficult airway. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2014;112 (4) 773-774.

- Chrimes, N. The Vortex: striving for simplicity, context independence and teamwork in an airway cognitive tool. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2015; 115 (1) 148-149.

- Watterson, L., Rehak, A., Heard, A. et al. Transition from supraglottic to infraglottic rescue in the “can’t intubate can’t oxygenate” (CICO) scenario. Report from the ANZCA Airway Management Working Group. 2014; Vortex Approach referenced p25, 39, 41, 45 and 50.

Leave a reply